Global attention to First Nations art is on the rise, with numerous institutional exhibitions and climbing auction prices. Last week, at Frieze in London, visitors could also see work by a key First Nations artist, on view with a major international dealer in the field, D’Lan Davidson.

The gallery was participating in Frieze Masters for the second consecutive year. “This is a big event on our calendar,” said Davidson in a phone interview. “There’s no question about the exposure that Frieze Masters gives us. We’re truly thrilled to be here.”

The booth was devoted to paintings and works on paper by Gija artist Goowoomji Nyunkuny Paddy Bedford (1922-2007). With 15 paintings that span his career, from 1998 to 2004, it highlighted his most important subjects, including contemporary history and dreamtime narratives. The paintings appeared alongside 20 gouaches on paper, a medium Bedford was introduced to in 1998 and that became part of his daily practice. These came from the artist’s estate, which D’Lan represents.

Installation view of “Paddy Bedford; Spirit & Truth” at D’Lan Contemporary at Frieze Masters, London. Photo: Dan Weill. Courtesy D’Lan Contemporary.

On the fair’s opening day, the gallery sold seven paintings and six gouaches for total of $1.3 million.

Bedford is not the only artist D’Lan exhibits who is earning accolades. Emily Kam Kngwarray (1910–96), whose work D’Lan Contemporary featured prominently at Frieze Masters last year, is the focus of a major show planned for Tate London in 2025.

First Nations and Aboriginal art from Australia have long enjoyed a loyal, if niche, following. Recently, actor and ardent collector Steve Martin garnered exposure for these artists via loans to major exhibitions, including one at the Gagosian gallery in New York in 2019.

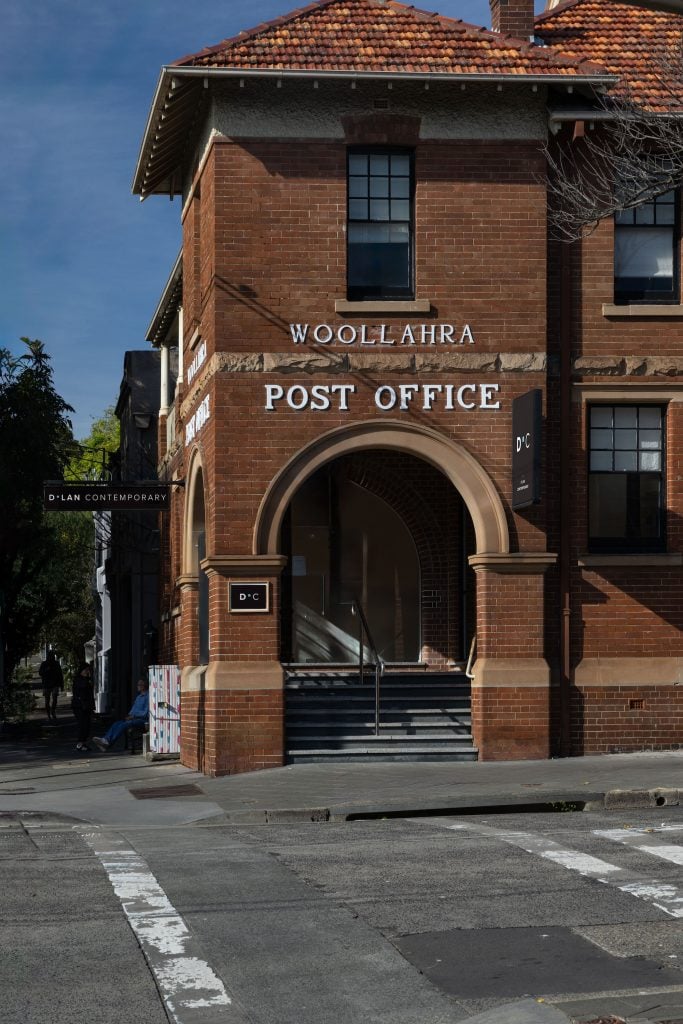

D’Lan Contemporary will open a new gallery in Sydney, Australia in November. Courtesy D’Lan Contemporary.

Davidson entered the field long before it received mainline attention. After starting out as a private dealer, he joined Sotheby’s Australia as head of Aboriginal art in 2010. He opened D’Lan Contemporary in 2016 and currently operates galleries in New York and Melbourne.

Now, he is gearing up for the launch of a Sydney gallery next month. Located on Queen Street, in Woollahra, it will span the ground floor of the historic Woollahra post office, which was formerly occupied by Bonhams. The first show will present Modern and contemporary art by leading First Nations artists such as Uta Uta Tjangala, George Tjungurrayi, Bill Whiskey Tjapaltjarri, Eubena Nampitjin and Carlene West.

The field has not been without controversy. In a 2007 report, the Australian parliament acknowledged concerns about “the integrity of art works that are sold [and] the conditions under which those works are produced and traded.”

D’Lan said he has aimed to help address these issues. His gallery contributes 30 percent of net profits to artists’ communities, supporting travel for artists as well as museum acquisitions. He is working with Indigenous governing bodies to create a central trust that will distribute these contributions.

Installation view of “Gunybi Ganambarr: Gapu-Buḏap – Crossing the Water,” at D’Lan Contemporary, New York, 2024. Photo: Peter Zowlinski. Courtesy D’Lan Contemporary.

In 2021 the gallery first established a fund that distributed sales proceeds to Indigenous artists and their communities. “But we found that the fund was difficult to access, particularly when communities really needed it,” said Davidson. “Art sales are often the main or only source of non-government income for remote Indigenous Australian communities. However, the primary and secondary Indigenous art markets do not currently generate sufficient revenue to support artists and their working communities.”

A bright spot in the market occurred five years ago, Davidson said. Previously, under Australia’s Protection of Movable Cultural Heritage Act, rules were very different for First Nations art and non-Indigenous art, he said. For First Nations work, anything over 25 years old and valued above AUD$10,000 (about $6,700) required an export permit, whereas only non-Indigenous art over 35 years old and valued above AUD$250,000 (about $168,400) needed one. Australia has altered the guidelines to correct that disparity, Davidson said, and the change did exactly what it was meant to do.

“It basically created free trade,” he said.

No Comment! Be the first one.