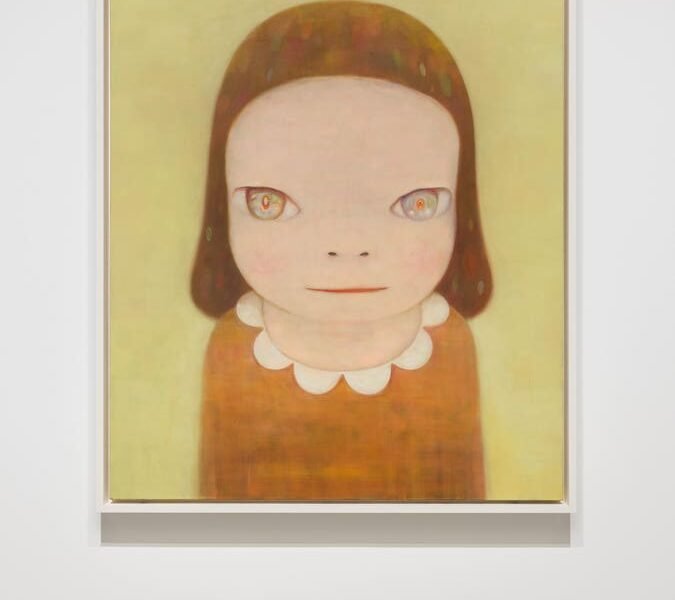

Installation view of Yoshitomo Nara. Miss Margaret, 2016. Photo Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery.

© Mark Blower 2025

Summer in London is synonymous with culture and I’ve selected four exhibitions that capture the dynamism and diversity of contemporary art. From the spiritual abstract landscapes of Emily Kam Kngwarray at Tate Modern to the emotionally resonant figures of Yoshitomo Nara at Hayward Gallery, the visceral brilliance of Jenny Saville at the National Portrait Gallery, and the glorious sprawl of the RA’s Summer Exhibition, these are all unmissable exhibitions.

Emily Kam Kngwarray at Tate Modern (until October 13th, 2025).

Emily Kam Kngwarray installation view at Tate Modern 2025 © Emily Kam Kngwarray Copyright Agency. Licensed by DACS 2025. Photo © Tate (Kathleen Arundell)

© Tate (Kathleen Arundell)

Tate Modern’s groundbreaking retrospective of Emily Kam Kngwarray marks the first major solo exhibition in Europe dedicated to this singular Australian artist. Kngwarray, a senior Anmatyerr woman born around 1914 in the remote Sandover region of the Northern Territory, did not begin painting until her seventies. Yet in the final decade of her life, she produced a formidable body of work that fuses cultural tradition, abstraction, and a deeply personal visual language.

Her work stems from her ceremonial and spiritual relationship with her ancestral Country, Alhalker. These are not simply landscapes, but manifestations of knowledge systems, rituals, and ecological stewardship. Early batik works from the 1970s are featured alongside her breakthrough acrylic paintings from the late 1980s, including Emu Woman (1988), a seminal canvas that catapulted her to national recognition.

The exhibition–curated in collaboration with the National Gallery of Australia–showcases over 70 works, many never exhibited previously outside Australia. Installations of her large-scale batiks drape like banners of Country, while her paintings, such as Ntang Dreaming (1989) and Ankerr (Emu) (1989), use earthy ochres and rhythmic dot patterns to depict food sources, waterholes, and migratory paths.

Emily Kame Kngwarreye’s middle name, “Kame,” is derived from the Anmatyerre word for the pencil yam, a plant particularly significant in her culture and art. Specifically, “Kam” refers to the seeds of the pencil yam (Anwerlarr). The Kam is not only a food source but also a central motif in her paintings, representing her connection to the land and her cultural heritage.

At the exhibition’s heart lies The Alhalker Suite (1993), a panoramic cycle of 22 canvases that offers a kaleidoscopic vision of her homeland. With hues ranging from pastel pinks to stormy blues, it’s a dazzling evocation of seasonal change, flora, and the eternal life force known as Altyerr. Although Kngwarreye began making art as such an advanced age, and lived in a region so removed from the contemporary art world, her incredible talent for translating natural phenomenon into works of art evokes the ability of the Impressionists to capture nature and light on canvas. Observing Kngwarrey’s paintings after watching footage of Alhalker, one can see how she has so cleverly conveyed the essence of the natural world in her homeland using natural pigments and an incredible sense of light and movement. Experiencing The Alhalker Suite could almost draw comparisons with seeing Monet’s Water Lilies. Bridget Riley’s abstract reimagining’s of the sun-drenched fields of Provence in high summer also come to mind. Kngwarrey’s paintings ping and vibrate with energy and movement, and the sheer volume of work she created is quite mind-blowing. Her late works–especially Untitled (Awely) (1994) and Yam Awely (1995)–show a bold shift to gestural abstraction, stripping her forms to a lyrical essence.

This exhibition isn’t just about an artist’s career; it’s about a worldview conveyed through pigment and pattern. It is a rare opportunity to experience an artist who painted not for the market or the academy, but to honour land, law, and legacy.

Yoshitomo Nara at the Hayward Gallery (until August 31st, 2025).

Installation view of Yoshitomo Nara. Photo Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery.

Mark Blower

Yoshitomo Nara’s first UK public gallery solo show is long overdue, and the Hayward Gallery has delivered an emotionally charged retrospective that captures four decades of the Japanese artist’s evolution. Known for his iconic depictions of wide-eyed, childlike figures who oscillate between vulnerability and defiance, Nara’s work is much deeper than its deceptively simple style suggests.

Organised thematically, the exhibition delves into Nara’s formative influences–from his solitary childhood in Japan’s Tōhoku region listening to American folk and protest songs, to his transformative years studying in Germany, where he absorbed the emotional immediacy of Neo-Expressionism. In the first, high-ceilinged room of the Hayward Gallery, the exhibition starts with a life-sized recreation of Nara’s studio, situated in a handmade shed-like construction, a painting hanging on the exterior depicting a small child standing on verdant green grass against a blue sky, with the words Place Like Home painted in rainbow colours, indicating that the shed-studio is Nara’s happy place. Visitors can peer through the windows to see the tools of the artist, pens, pencils, paper, and things that inspire him as he works–from kitsch toys to favourite music. On the wall beyond the shed is a vast display of vinyl, including records that have inspired and informed Nara’s work over the years, from folk music to psychedelia to rock and punk.

What unfolds as you journey through the galleries is a story of quiet resistance. Nara’s figures, often rendered with minimalist brushwork and haunting stillness, become avatars of innocence, trauma, and rebellion. Works like Ships in Girl (1992) reject the saccharine tropes of kawaii culture, instead offering nuanced portraits of psychological unrest. Meanwhile, From the Bomb Shelter (2017), created in response to the 2011 Fukushima disaster, introduces a more sombre tone–a child emerging cautiously into an uncertain world. Sadly this image strongly resonates now, in an era when too many children are still at the mercy of war and conflict. Images such as No War, No Nukes and Stop The Bombs–which shows a child-like figure holding a placard with an anti-war mantra dating back to countercultural movements of the 1960s–are still deeply pertinent now. Nara first came across the anti-war movement during his childhood–when he lived among the US military bases from where soldiers were dispatched to fight in Vietnam–and he heard political folk music and protest songs on the radio.

Nara’s more recent paintings, such as Midnight Tears (2023), feature tender, fragmented brushwork that radiates introspection. Nara has an incredible ability to paint eyes that are like windows into the soul of his child-like figures, pools of introspection with reflections of pain inflicted on innocents by the outside world. For this painting–which is on loan to the Hayward Gallery exhibition from the Guggenheim Bilbao–Nara revisited the techniques he learned at art school in Dusseldorf of the German Neo-Expressionists, which involved the application of layers of wet-on-wet acrylic paint.

The influence of music remains palpable throughout–punk, folk, and blues notes echo in his palettes and postures. While sculpture, collage, and works on paper provide a broader understanding of his practice, it is the paintings that hold viewers in their silent, resolute gaze.

Curator Yung Ma calls Nara “iconic,” and it’s hard to disagree. This exhibition is not just a survey–it’s a meditation on loneliness, memory, and the redemptive power of making art.

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting at the National Portrait Gallery (until September 7th, 2025).

Jenny Saville, Drift, 2020–22. Courtesy National Portrait Gallery.

Courtesy National Portrait Gallery

Few contemporary artists capture the brute force and fragility of the human body like Jenny Saville. In The Anatomy of Painting, the National Portrait Gallery presents a deeply personal and chronological journey through the work of one of the most influential painters of the past 30 years.

From her audacious breakout piece Propped (1992) –a self-portrait that snarls at convention—to her recent abstract experiments, the show underscores Saville’s ability to oscillate between flesh and feeling.

Saville’s confrontational large-scale paintings caught the attention of art collector Charles Saatchi, who purchased her work shortly after she graduated from Glasgow School of Art, and she became associated with the Young British Artists (YBAs), featuring in seminal exhibitions Young British Artists III (1994) and Sensation (1997).

Her large-scale oil paintings are monumental, both in size and emotional depth. Bodies twist, sag, bleed, and assert themselves unapologetically. She paints not with delicacy, but with urgency–every brushstroke an excavation of vulnerability.

Saville’s practice is steeped in anatomical study. Her fascination with the body’s structure has led her to observe surgeries and dissect medical texts, giving her portraits a topographical depth few others achieve. And yet, in later works, she turns inward, toward the anatomy of painting itself–gesture, tempo, layering. Her influences–including Tintoretto, Titian, Bacon, Freud, de Kooning, and Twombly–are evident, but Saville’s voice remains utterly her own.

The inclusion of charcoal drawings and intimate works on paper adds tenderness to the exhibition. A rainbow wash across a face; the suggestion of a skull beneath translucent skin–Saville invites us to inhabit these bodies as sites of transformation.

Thoughtfully Curated by Sarah Howgate–NPG Senior Curator, Contemporary Collections– Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting brings together 45 works tracing the artist’s prolific career, creating a landmark show that proves Saville isn’t just painting bodies–she’s capturing the essence of our psyche.

Royal Academy of Arts Summer Exhibition (until August 17th).

Sikelela Owen ‘Knitting’

Sikelela Owen

Every summer, the Royal Academy’s sprawling Summer Exhibition turns the neoclassical halls of Burlington House into a carnival of contemporary creativity–and the 257th edition is no exception. Co-ordinated this year by Royal Academician and architect Farshid Moussavi, the 2025 theme is Dialogues –a prompt that’s opened the doors to artists and architects exploring intersections between humanity, nature, and society.

This year, architecture is embedded throughout the show, forging visual and conceptual conversations with the art. Highlights include Alice Channer’s soaring 6m sculpture of ostrich feathers and steel chain, and Antonio Tarsis’ vast wall of reassembled matchboxes. Suspended works hang from the rafters–Tamara Kostianovsky’s fabric carcasses among them–challenging our sense of scale and materiality.

The exhibition remains proudly democratic, featuring submissions from unknown artists alongside Royal Academicians. Big names abound: Grayson Perry, Lubaina Himid, Cornelia Parker, and Yinka Shonibare all contribute, while Jenny Holzer and Marina Abramović appear for the first time as Honorary Academicians.

The Royal Academy of Arts recently announced its 2025 prize winners, which include Sikelela Owen who won the £34,000 Charles Wollaston Award for her beautifully contemplative painting, ‘Knitting’, based on a photo of her mother.

Other prizes included The AXA Art Prize (£10,000) for ‘an outstanding work of figurative art’, awarded to Miho Sato for her painting Windy Day 2, and the Jack Goldhill Award for Sculpture (£10,000), which was awarded to Zatorski + Zatorski for their sculpture created from 101 white rat pelts filled with 24-carat gold.

New architectural commissions by 6a architects, JA Projects, and 51 Architecture–whose 6m-high wildlife roost graces the courtyard–reflect the RA’s commitment to sustainability and social engagement. But the Summer Exhibition is also about joy, discovery, and tradition. Ryan Gander RA’s inflatable balls, inscribed with childlike absurdities, welcome visitors with a spirit of play and curiosity. Sales from the show support the Royal Academy Schools, the UK’s only free postgraduate art program.

It’s chaotic. It’s crowded. It’s brilliant. And it remains one of the most vital celebrations of art in the country.

Gallery view of the Summer Exhibition 2025, at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, 17 June – 17 August 2025. Photo © Royal Academy of Arts, London / David Parry.

© Royal Academy of Arts, London / David Parry.

Final Thoughts

Whether you’re tracing ancestral stories across the desert canvas, locking eyes with a punk-infused child-ghost, peeling back layers of pigment and flesh, or wandering through a riotous gallery of ideas, London’s summer exhibitions invite you to see, feel, and reflect. Each show is not just a display of art–but a conversation: between cultures, between disciplines, and between past and present.

No Comment! Be the first one.