Most Australians have heard of Norman Lindsay’s fantastical children’s book The Magic Pudding (1918).

Norman was one of ten talented siblings, many of whom became internationally renowned artists and writers during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Lindsays were one of most culturally influential middle-class families in Australian history.

How did a group of middle-class kids from a country town come to have such an impact on a national culture? Numerous studies have focused on individual Lindsays’ lives and careers, but few scholars have thought about the siblings as a collective.

Examining the Lindsays as a group reveals the secret to their success lay in the artistic culture developed by the siblings in childhood that led to powerful creative and social networks in adulthood.

An artistic childhood

The Lindsay brood grew up in the west-central Victorian town of Creswick in their home Lisnacrieve, overseen by their strict, religious mother Jane, and their less watchful, somewhat indulgent father, Robert Charles.

Between 1870 and 1894, ten children were born: Percival (Percy), Robert, Lionel, Mary, Norman, Pearl, Ruby, Reginald, Daryl and Jane Isabel. Five became professional artists.

Image © Art Gallery of New South Wales

Landscapist Percy took inspiration from his hometown’s surroundings for his oils.

Lionel devoted his talents to printmaking and gained local and international renown for his woodcuts and etchings. Norman was a multi-medium artist and author.

Ruby drew delicate illustrations for popular books and magazines. And Daryl painted equestrian and outback scenes before taking on the directorship of the National Gallery of Victoria.

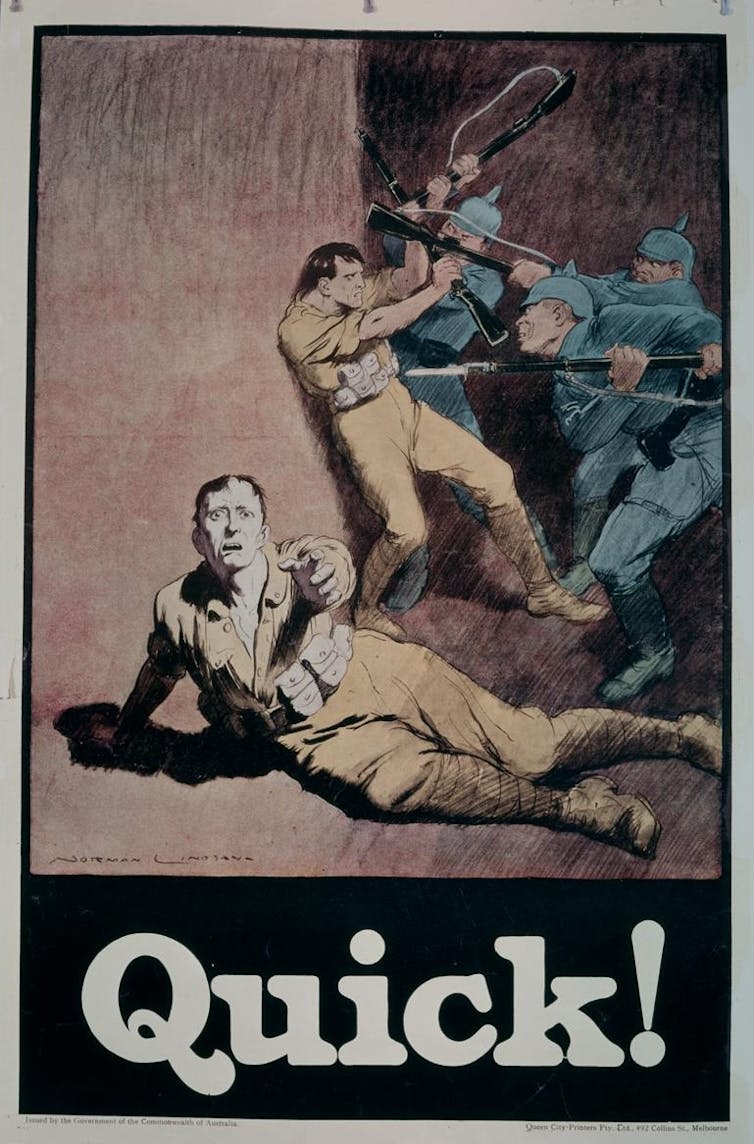

State Library Victoria

Domestic life was not always blissful at Lisnacrieve.

Brothers fought, sisters bickered and others (particularly second-born Robert, “a delicate child” as described by Daryl) felt left out of the sibling dynamic.

Despite tears and tumult, the relationships between the Lindsay siblings were their closest, most constant bonds. Family loyalty and duty acted as a bulwark against external intrusions. Daryl recalled in his memoir “despite our private rows at home” his older brother Reg would “knock the head off any boy who laid a hand on me at school”.

These bonds fostered the young Lindsays’ creative development with their own culture focused around reading, art and play.

National Portrait Gallery of Australia.

The siblings inspired one another’s artistic imaginations. The elder suggested what books the younger should read – Lionel’s library fed Norman’s literary tastes and inspired his early drawings. Brothers provided criticism of each other’s art. Mary, prevented from pursuing her interest in writing by their mother, financially supported Ruby to attend art school.

The siblings played together. Along with friends, they partook in musical evenings at home, singing operas and performing comedic skits and tableaus. They embarked on imaginative games, pretending to be soldiers or gold prospectors.

State Library of New South Wales

Nascent racism often underscored the Lindsay boys’ relentless pursuit of entertainment. In his recollections of visiting the Creswick Chinese camp, Daryl described the residents as a source of “amusement”. These attitudes would inform some of the brothers’ later artistic work.

Nevertheless, the unique culture cultivated by the young Lindsay siblings went on to inspire and support their adult endeavours.

The life of an artist

Beyond the creative furnace of Lisnacrieve, the siblings sustained their relationships by forging economic, professional and social networks.

From 1890 until around 1914, the siblings became embedded in Melbourne and Sydney’s bohemian art scenes. This was a period of intense interdependence between Lionel, Norman, Percy and, later, Ruby.

State Library of Queensland

The siblings negotiated public life together. They ran in the same social circles, championed one another’s work, shared employment opportunities, negotiated business deals, exhibited together and often shared accommodation.

The Lindsays’ writings and drawings populated the pages of Australia’s most significant cultural magazines including The Hawklet, Free Lance, Clarion, Tocsin and Rambler in Melbourne, and later The Bulletin and The Lone Hand in Sydney.

The sibling networks helped them to mediate historical change, articulating and facilitating rising national sentiment in their work.

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

The Lindsays helped to create a national pictorial identity emphasising childlike imagination and comedy, as well as classical and romantic literature. Their cartoons and artworks gave artistic expression to racist, misogynistic and antisemitic attitudes pervasive among white Australians at the time.

In 1901, Australia federated and Norman started working at the country’s most prestigious illustrated magazine, The Bulletin, where Lionel joined him in 1903.

National Archives of Australia

Here, Norman cultivated a reputation as the finest illustrator in Australia, representing the magazine’s nationalist and conservative editorial policy. First Nations people, Chinese and Jewish migrants were caricatured, mocked and belittled, set outside the boundaries of ideal citizenship.

Creative rivalries

Over time, creative rivalry threatened the strength of sibling ties, particularly between the once close-knit Norman and Lionel.

Norman’s decision to use private family narratives as fodder for his 1930 novel Redheap – a tale of siblings growing up in country Victoria – without family consultation fuelled enmity.

This betrayal also unearthed childhood and early adult animosities. Lionel’s envy of his brother’s talent and success, and the sacrifices he made to propel Norman’s career, lay beneath his assertions of disloyalty.

Yet even during periods of distance and ill feeling, the Lindsays were fundamental to one another’s lives.

State Library of New South Wales

In a letter to Lionel in 1917, Norman wrote of the profound “long intimacy” between them:

For no growing old should spoil it: this is the one and most important thread in our lives.

Understanding this “thread” of the Lindays’ shared childhood and relationships is fundamental to mapping the trajectory of their careers and personal lives.

It is also key to comprehending the central role this family, and, by extension, sibling networks, played in fashioning Australia’s cultural imaginary – perpetuating the often nationalist and racist story Australia wanted to tell about itself at the turn of the last century.

No Comment! Be the first one.